Eating Europe Week 12

PALERMO, SICILY— The longer I stay in Italy, the more I want to pitch a tent, skip the rest of the countries on my yearlong list, and dive into the Italian food and culture as deeply as I can.

France, Spain, and a dozen other countries with storied cuisine and customs lie ahead, but I have a hard time convincing myself that the time I spend there will be better than this.

I love the regionalism of Italy.

Amalfi, and the craggy, vertical coastal towns above and below it host some of the most beautiful sunrises and sunsets I have ever witnessed. The food was good, lemons made frequent appearances on menus, and seafood was plentiful.

Many of the Amalfi fishermen work alone in small wooden boats. They fish in the early hours of the morning, load their catch in ice chests precariously strapped to the backs of a battered scooters, and head to the fish market.

From Amalfi, we worked our way south into Sicily where we spent two, mostly uneventful, nights in Modica. I was told by many to spend the majority of our time in the southeastern portion of the island. After two days, I ignored that advice and headed west towards Marsala and Palermo.

The drive from Modica to Marsala was filled with dramatic coastlines, olive trees, grapes, and tomato vines. This region appears more agrarian than any other we have visited in Italy. The latitude is equivalent to North Carolina or Virginia, but Southern Italian crops are grown year round.

One will hear several explanations defining the difference between Northern and Southern Italian cuisine. Some boil it down to the usage of butter in the north and olive oil in the south. But it goes much deeper than that.

Actually, there is no gastronomic dividing line between Northern Italy and Southern Italy. The preferences in ingredients and tastes occur organically and are based on centuries of local traditions.

It’s all local. The preferred foods of a particular region are the ones that are raised, grown, and harvested by the people in that area. That is the beauty of Italian cuisine.

Though the cream/olive oil explanation is partially true— the farther south one travels the less dairy he or she will find. In the central regions of Tuscany and Umbria, they frown on cream sauces in pastas, but use plenty of it in their coffee. Most Western Sicilian restaurants don’t even have cream or milk available for after-dinner coffee. It’s black and that’s that.

The key to the system is the local factor. It goes back centuries to Italy’s former city-state divisions. Every region grows its own specialties, and those ingredients are featured prominently in the cuisine of that town or region. For years, before mass transport and bulk shipping, they had no choice. Things haven’t changed too much, and they like it that way.

The localism of the cuisine even breaks down within a region. Tuscany is known for white beans, but each town or municipality has their version of how the beans should be prepared.

My wife, Jill, and our friend David order wine in restaurants by saying “white” or “red.” The trattorias and ristorantes have wine lists, but they are rarely used. The popular wines are the ones produced within a few kilometers of the town— usually by a friend of the restaurant’s owner. The most common phrase heard is, “di questa zona.” (of this area). That is usually followed by, “It’s the best.” Oftentimes, “It’s the best in all of Italy.” Regional pride only adds to the charm.

Olive trees are grown in two-thirds of the country, but the region, town, or area in which you are currently dining has the “best” olive oil. It’s hard for an American to argue the point. I’ve enjoyed excellent olive oil in every region we’ve visited. I love the pride that Italians proudly display in the products produced and cultivated near their home.

It’s no great shock that the restaurants here in western Sicily specialize in seafood. The fresh catch is typically displayed in the dining room. The local fish varieties that were caught that day are displayed as whole fish on a platter, cart, or small buffet table. One chooses the fish he would like to eat and the preparation by which it will be cooked, and a server takes it to the kitchen where the chef cleans it, cooks it, and sends it to the table. Beautiful.

Most of the restaurants in this area have dozens of antipasto trays displayed in the dining room. Marinated eggplant, squid salad, artichokes, mushrooms, cous cous, rustic savory pies and tarts, olives, pickled vegetables, anchovies prepared several ways, and a dozen other antipasti are available. One could make a meal out of antipasto, but one never does.

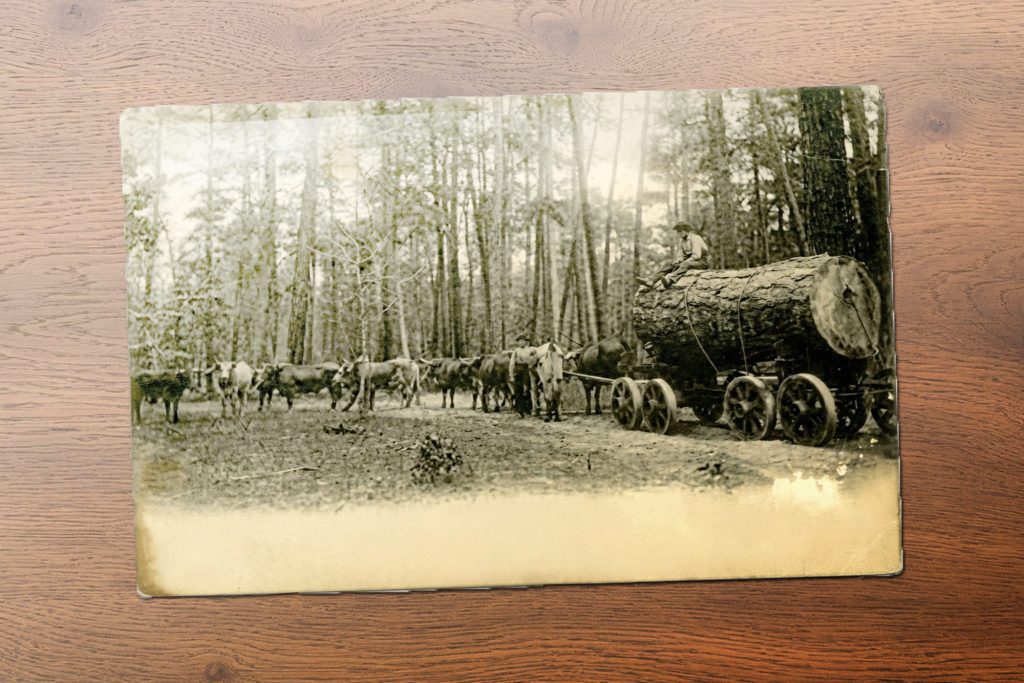

Several months ago, we traveled the Romantic Road in Germany. Two days ago, we made our way down the Salt Road from Marsala to Trapani. While skirting the Mediterranean one is suddenly confronted with massive mountains of snow-white sea salt drying in the sun. We toured a facility that mills sea salt the way it was done hundreds of years ago using nothing more than the sea, the sun, wind, and a little manpower.

The area has the perfect combination of shallow water, salinity, intense summer heat, and high wind. Salt collection and production in that particular area goes back to the Phoenicians, and no one is surprised when the Trapani sea salt is described as “the best” in the world. Again, it’s hard to disagree.

The owners of Ettore e Infersa Salt Works have reconstructed a 500 year-old Dutch windmill to help pump water from the deep (cold) flats to the shallow ones, and no stopover to this area should be without a visit to their operation.

Tomorrow we board a ferry and begin to make our way towards Venice, Milan, and eventually Lake Como. There we will once again dive into the food of the north, where it is a little more refined, but still di questa zona.

Fried Eggplant

12 Eggplant rounds

1 cup Flour

2 Tbl Creole Seasoning

1 Egg

1 /3 cup Milk

1 1 /2 cups Seasoned breadcrumbs

Peanut oil for deep-frying

Peel eggplant and cut into round discs, about the circumference of a mayonnaise jar lid and cut 1 /4 to 1 /2-inch thick. Marinate eggplant in salted, lemon ice water until ready to cook.

Combine flour and Creole seasoning.

Combine egg and milk.

To fry eggplant rounds; lightly dust in seasoned flour, shake off excess, dip in the egg wash, and coat with breadcrumbs. Fry a few at a time at 350 degrees until medium brown and crispy. Do not overload the oil. Drain on paper towels.

Yield: 12 servings