Author’s Note:

Robert St. John’s Mississippi Christmas hit the shelves a couple of weeks ago (click to purchase). It’s a collection of recipes and stories from the Christmases, the people, and the neighborhood that shaped me— and the ones still unfolding. The piece below didn’t make the final edit, not because it fell short, but because its heart shows up in several other places throughout the book. Even so, it has become a steady part of my readings on the book-signing tour.

Some families grow up with postcard Christmases—crackling fires, golden retrievers by the hearth, snowflakes on the St. Augustine. Then there was us. Our holidays were about as “Hallmark” as a ham sandwich on white bread.

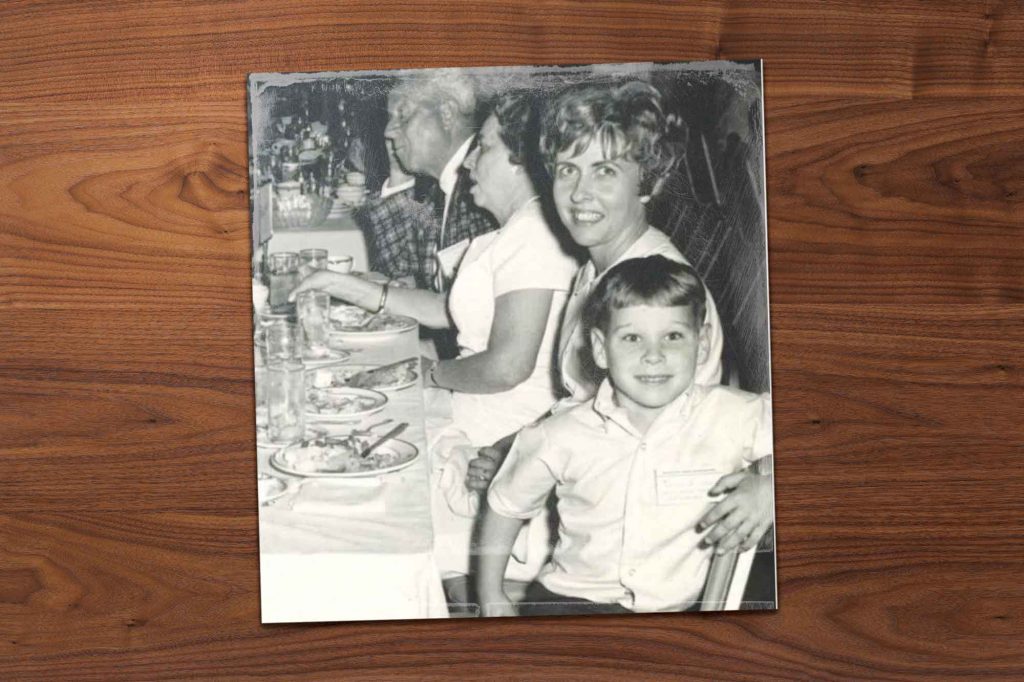

We didn’t have much money, and we didn’t have a dad in the house. What we did have was love, a dozen casseroles, and a mother who believed in Christmas like preachers believe in Sunday.

My mother was a public-school art teacher—creative, underpaid, and armed with enough oil paint, pottery clay, and turpentine to rebuild Bethlehem from scratch. She didn’t have a budget for fancy decorations, so she leaned on imagination and child labor. My brother and I were her two-man decorating crew, compensated with cookies and guilt.

Which brings us to the tinsel.

Icicles, as we called them, were sacred. Every year my mother bought boxes of them by the gross. My family believed in tinsel the way Methodists believe in covered-dish suppers: not optional, and the more the better.

My brother and I would stand in front of the tree, hurling handfuls of icicles with the precision of a Mardi Gras float crew. The goal wasn’t beauty—it was density. If you could still see green, you were failing.

Our across-the-street neighbor, Jimmy McKenzie, had an entirely different philosophy. Jimmy placed his icicles on one at a time, straight as law, as if the whole neighborhood was grading him on neatness. His kids would sneak over to our house for a hit of chaos. “Can we throw some with y’all?” they’d whisper, and my mother, Christmas outlaw that she was, would hand them fistfuls like contraband. Within minutes, our living room looked like Liberace had moved in for the season.

It was a glorious, glittering fire hazard.

Looking back, it was the perfect symbol of my childhood Christmases—messy, homemade, and full of love that wasn’t worried about getting it right, just getting it real.

Our home on Bellewood Drive wasn’t the kind of place you’d see in a Rockwell-inspired snow globe. For starters, there was no snow. If we ever woke up to a white Christmas, it was because Hattiesburg decided to pretend for a morning. Ten houses, one dead end, and a neighborhood watch system powered entirely by gossip—but that little street had more Christmas spirit per square foot than Rockefeller Center.

There was Larry Foote, who roasted pecans so perfectly they didn’t last long enough to cool. A banker by trade, he turned into a pecan-centric master chef every December. His salty pecans were everywhere—you couldn’t walk into a room without finding a bowl of them within reach. His wife, Barbara Jane, perfected the cinnamon roll.

Across the street lived Mary Virginia McKenzie— wife of the fastidious icicle specialist— whose orange sweet rolls were the unofficial currency of Bellewood Drive. The whole neighborhood knew when her oven was on. That smell made you believe in second breakfasts.

Next door lived the Webb sisters—three old maid retired schoolteachers with matching bouffants—whose gingerbread never made it to Christmas Day. They also handed out fruitcake cookies to every child in the neighborhood. That’s how I learned what disappointment tasted like.

Mom was the holiday general holding this whole operation together. She was raising two boys on a public school art teacher’s salary that could barely feed one Cocker Spaniel, but she never let that slow her down.

She never talked about what we didn’t have—she just made what we did have enough. I never realized how broke we were because everything we needed always showed up—usually in Pyrex.

If you ran out of sugar, someone had extra. If your lights blew out, neighborhood men appeared with ladders and more confidence than wiring knowledge. Christmas wasn’t just a holiday; it was a community sport.

Every kitchen on Bellewood Drive glowed warm and smelled like butter and something frying that probably shouldn’t be. The air was thick with cinnamon, bacon grease, and cigarette smoke—the official scent of a Hattiesburg December.

Even the noise told a story—laughter from back yards, a dog barking, and somebody calling everyone to the table.

When I grew up and opened restaurants— all a few blocks from my childhood home—Christmas changed shape. The season meant payroll stress, late-night closing shifts on the line, and staff parties that occasionally ended with a visit from the police. But even then, the old light found a way through—a regular guest dropping off a tin of cookies, a server handing me a handmade card that said, “Merry Christmas, Boss. Thanks for the job.”

These days, my house looks nothing like the home I grew up in. The lights all work. The turkey is moist (thank you, brining). The mashed potatoes are from scratch because I can finally afford the luxury of lumps. But when the family piles in, the noise settles into a sound I’ve known my whole life. There’s still too much food, too many opinions, and always, always love.

Mom’s been gone for over a year, and most of those neighbors have traded casseroles for glory. But I still make Larry Foote’s pecans. My bakery bakes Mary Virginia’s sweet rolls. And sometimes, when I dig through old decorations, I find a single strand of tinsel wrapped around one of my great-grandmother’s handmade felt ornaments, still hanging on, same as the memories.

Back then, tinsel was just something shiny to throw on a tree. Now it feels more like proof we were doing our best to make things bright.

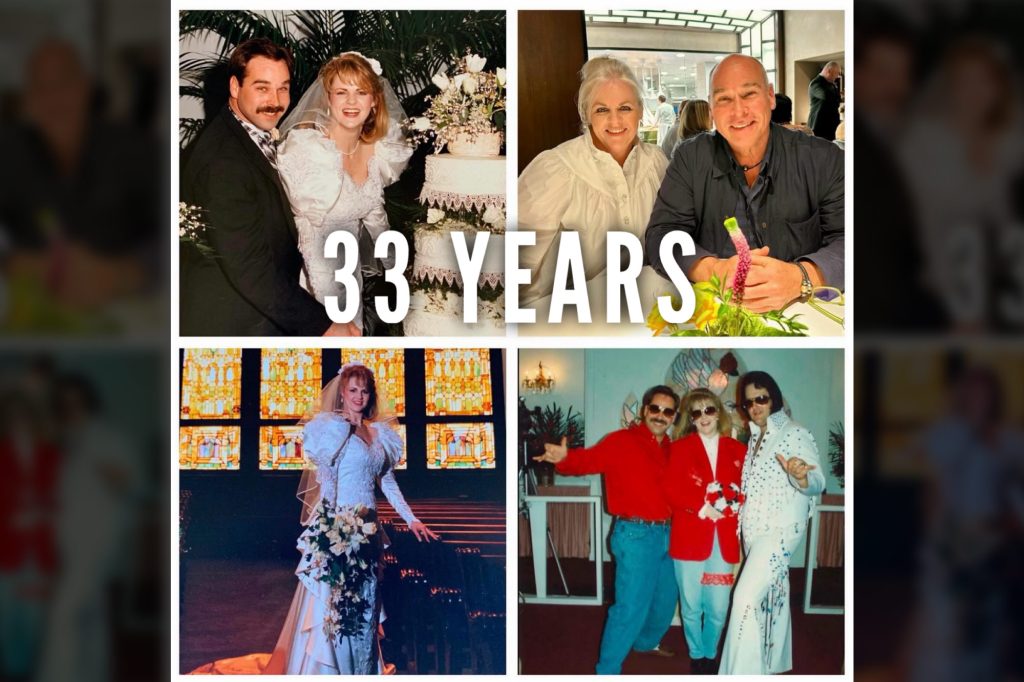

My wife prefers minimalism—“tasteful,” she calls it. Her first reaction to my family’s tinsel tradition was pure horror. She said it looked like Elvis had been in charge.

I took it as a compliment.

For years, we fought the Great Icicle War—she’d hide the tinsel, I’d find it. She’d remove it strand by strand; I’d replace it when she wasn’t looking. Our kids grew up Switzerland—neutral but amused, sneaking on a few strands when she left the room just to keep the peace. In the end, the wife won. The tree’s gone upscale—Radko ornaments and all. I don’t know anything about the Radko guy, but whoever he is he’s a little too proud of his product which is still no match for my great-grandmother’s sequins and thread.

In my mind’s eye I can still see my old street—porch lights glowing, voices carrying down the pavement, and the smell of something sweet in the air. The world felt smaller then, but somehow fuller.

If you ask me, Christmas doesn’t need snow, or pricy ornaments, or even working lights. It just needs a place like Bellewood Drive—where the food was honest, the neighbors were close, and love was just part of the block.

And I still believe that somewhere, under those old loblolly pines, that street is glowing. Maybe not on a map. But in the kind of light you carry with you the rest of your life. The kind of light that first lit up a manger — simple, warm, and full of hope.

Ours started on Bellewood Drive — a handful of houses, a mountain of casseroles, and enough love to make up for the rest.

And not a snowflake in sight.

Onward