“He was a brave man that first ate an oyster”— Jonathan Swift

The “food firsts” in my life have all been memorable. I remember the first time I ever ate lamb. Actually, I remember the first time I was ever told that I was eating lamb. I had actually been eating it for years, but the adults in my life had banded together to tell me it was “roast beef” because I had refused to eat lamb the first time it was served to me. Eventually, they broke the news to me, and I was finally let in on the long-held family secret.

I can remember the first time I ever ate Benton’s bacon, the first time I ever ate parmesan-truffle fries, and dozens of other “first” items all across the European continent. Though one of the most significant food firsts in my life was raw oysters.

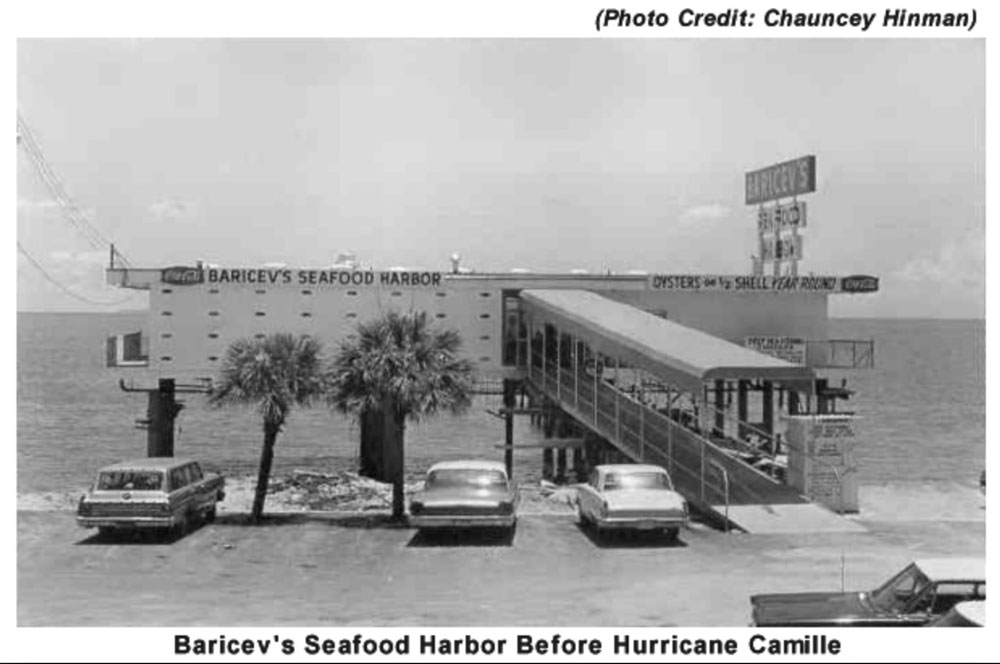

I can easily remember the first raw oyster I ever ate. It was at Baricev’s restaurant on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, and I was sitting at the oyster bar with my grandfather and my brother. My father died when I was young (I am told he, too, was a huge fan of raw oysters) and my grandfather was the primary male influence in my life.

My attitude towards eating raw oysters wasn’t a typical one for an eight-year-old kid. No one had to force me— and my terrified, tear-stained face— to try an oyster. There was no drama or wailing and gnashing of teeth in the restaurant. I had asked to sit at the oyster bar to try my first oyster. My older brother had already been eating them for a few years, and he was a huge fan. I looked up to him as much as I looked up to my grandfather (who was a world-class oyster eater), and so I was ready to get started on a long, full, life of raw-oyster eating.

Baricev’s was owned by one of the Croatian/Yugoslavian fishing families who had migrated to the Mississippi Gulf Coast near the turn of the last century. All of those Slavic immigrants were fishermen on the Adriatic Coast and were a step ahead of other immigrants when they began dropping nets in the water over here.

Many of them opened restaurants, too. My grandfather’s favorite— and therefore my favorite— was Baricev’s. There was a “grown-up” feeling I had sitting up at the oyster bar with my grandfather and brother, while my mother and grandmother were back at the table in the dining room. There was a sense of independence. Even though my mother liked oysters, this felt like a “man thing.” Growing up without a father in the home, this might have been the first spark I ever felt of male bonding. It was great. The oysters were, too.

Fast forward 40 years, and I can remember the first time my eight-year-old son ate an oyster. As with me, there was no kicking and screaming. It was a tearless event. He might have been more enthusiastic about eating his first oyster than I was. We were in our New Orleans-themed concept and I had busted him out of school during his lunch break to go on a longer lunch break with me (a practice I did with both of my children once a week). I ordered a dozen raw as an appetizer and he asked if he could try one. I loaded one on a cracker and put a little extra cocktail sauce on it, and he ate it like a champ. He immediately ordered a half dozen raw for himself. And after he finished that half dozen, her ordered another half dozen.

The boy had knocked out a full dozen at his first seating. I was a proud papa. He still orders raw oysters, more times than not, when we eat in our restaurants that serve them. There are a few activities that are “ours,” things that the two guys do as father and son that we don’t do with my wife and daughter. Neither of us hunts or fishes more than once or twice a year. We don’t play golf or tennis. He, like his old man, enjoys movies, music, food, and football. I can watch a pee-wee football game from start to finish and not even know one player on the team. Eating raw oysters together, sharing a breakfast together, going to action movie matinees, and listening to 90s grunge and alternative music is our father-son thing.

Our family spends a lot of time throughout the year in New Orleans. The boy and I eat oysters down there a lot. He is a fan of Cassemento’s and begs to eat there if we are there during the months they are open. I used to eat at the Acme a lot until the Food Network and travel television blew it up to where there is always a line on the sidewalk.

My go-to these days for raw oysters, and my favorite oyster bar in New Orleans, is tucked into the corner of the front bar at Pascal’s Manale restaurant on Napoleon. The restaurant has been open for over 100 years, and is known for their barbeque shrimp, and might actually be the first place that ever served that particular dish (to be honest, I’m not a fan of their version even it might be the initial representation). Though I am a HUGE fan of their oysters and their raw bar.

When it comes to eating raw oysters at Pascal’s Manale, it’s classic New Orleans all of the way. One pays the bartender for how many oysters he wants, and the bartender hand the customer a small, custom logo’d poker chip. The customer then takes the chip over to the oyster shucker. For those not familiar with stand-up oyster bars, there is a marble counter about mid-chest level, with an oyster shucker standing on the other side. At his waist are a sack of oysters that have been emptied into an ice bin and are completely iced. Manale’s are consistently the coldest oysters I have eaten in New Orleans.

Tucked away in a corner across from the oyster bar is the condiment station with all of the usual players— hot sauce, potent horseradish, lemons, ketchup, Worcestershire, crackers, cocktail forks, and napkins. Everyone makes their own personal version of cocktail sauce. Mine is the same as it’s been since the first time I ate an oyster a half a century ago— ketchup, lemon juice, and a whole lot of horseradish. Seriously, my cocktail sauce for oysters is so loaded with horseradish that it has almost no red in it from the ketchup and is beyond pink and into the cream-colored spectrum with a dash of red. I don’t use hot sauce unless the horseradish is weak, and the farther one travels from New Orleans, the weaker the horseradish. For me, it’s ketchup, a lot of horseradish, and lemon juice.

I also like to squeeze lemon on the oysters while they are sitting in the shell, and also add a little salt to them. Pascal’s Manale’s horseradish is potent, so— to my taste— no hot sauce is needed. One stands at the oyster bar while the shucker opens the oysters. And places them on top of the marble bar directly in front of the customer. It’s the classic New Orleans way. One knows how many oysters he’s eaten by how many empty shells are stacked up in front of his spot at the bar.

There are several activities that we enjoy experiencing as a father-son team— football games, concerts, movies, and breakfast. Though eating raw oysters together seems to have a little more meaning, probably because of those early days at Baricev’s with my grandfather.

Onward.