WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA— It’s crunch time in the pre-opening phase of our new restaurant, but I peeled away to Virginia for two days. My brother and sister-in-law invited my wife and me to join them to see Bruce Hornsby and Alison Krauss perform at an outdoor festival up here. No one has to ask me twice when Kraus is involved.

I am a huge fan of Alison Krauss. I have seen the 27-time Grammy winner in concert several times but jumped at this chance when my brother invited us earlier this year. I have no idea what an angel’s voice sounds like— and I hope several decades pass before I find out— but if an angel’s voice sounds any purer than Krauss’, I will be pleasantly surprised once I pass through the pearly gates.

Folks, I love and adore my wife with all of my heart and have pledged my love and devotion until death do us part. I hope that we both live well into our 90s, and I hope to die one minute before she does, so I will never have to live without her. But I have also informed her that if, God forbid, anything should ever happen to her, I am likely to get arrested shortly thereafter for celebrity stalking Alison Kraus.

The concert was great, and I didn’t get arrested for stalking.

It has been almost 50 years since I have visited this town. I wrote about that last visit in the book “Deep South Parties” (Hyperion 2006).

My mother loves all things Early American and would if given the chance, travel back to the 18th century to live in Colonial Williamsburg.

A devout member of the Daughters of the American Revolution and the Colonial Dames, Williamsburg is her Mecca, the center of her universe. It guides her travel, it influences her reading. It is the basis for every decorating decision she has ever made or will ever make. No matter what the problem is, the way they did it in Colonial times is the solution.

She loves Williamsburg almost as much as she hates dirty hands. She is not a rupophobe, but she watches too much television, committing every news report involving germs or dirt to memory, and within hours publishes lengthy theses on cleanliness and Godliness which she passes out—double-spaced, typed, and in three-punch folders— to every member of the family.

Her love of all things Early American is in her bloodstream and molds her philosophical being. She wanted her two sons to grow up and attend The College of William and Mary, not because of any concern for our education, but for its proximity to Colonial Williamsburg

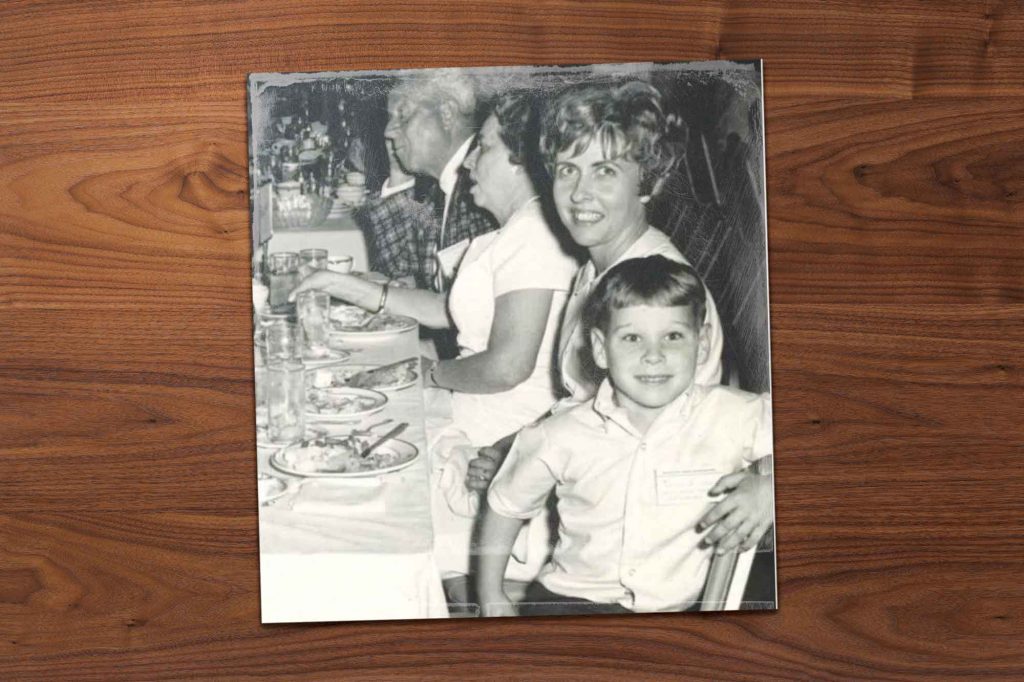

When I was seven-years-old she dragged us along on one of her many pilgrimages to the Early American Promised Land. We went willingly, but only based on the promise that we would also be able to visit Busch Gardens and ride the roller coaster.

We arrived in Colonial Williamsburg at the crack of dawn. Nothing had opened yet, but she didn’t want to risk missing a single thrill that might lay waiting in a simulated replica of an Early American village. As we walked through the cobblestone streets, I witnessed a transformation in her demeanor. She was wide-eyed and in awe. Weaving our way through the James Geddy House, she spoke under her breath, to no one in particular, “Things were just better back then.”

“But Mom, they pee’d in a bowl and kept it on a table in their room overnight.”

“It’s called a chamber pot, and just look at the craftsmanship and artistry of the bowl. It’s beautiful. Anyone would be proud to urinate in such a work of art. I’ll bet they always kept their hands clean.”

“But Mom, they had no air conditioning.”

“It was cooler back then, boys. Those were the days before global warming.” My mother, like the colonists, was early into environmental issues.

She bought us tri-cornered hats and made us wear them. It was 1969— the year in which bell bottoms reached their largest circumference and stack shoes attained their highest elevation— but there we were, at seven and 11-years old, wearing tri-cornered hats and souvenir-shop baby-blue waistcoats with our names stitched on the chest.

After the obligatory photograph of my brother and me locked in the stocks, and a visit to the town pillory, we went to the blacksmith shop where she bought me a horseshoe. “Did you wash your hands? You don’t know where that horseshoe has been.”

“But I do know where it has been, Mom. It’s been with us in the un-air-conditioned blacksmith shop for the last two and a half hours.”

After visiting a basket maker, a shoemaker, a brickmaker, and a wigmaker, we ended up watching a woman churn butter. No Busch Gardens. “You boys can ride a roller coaster anytime. This is history. Now go wash your hands.”

Traveling back to my mother’s mecca as an adult has been a great experience. As an adult, I can appreciate the sacrifices made by the early colonists, and the bravery and courage it took to forge a new nation. I can also appreciate how many pancake restaurants are located here. Williamsburg is a town of just over 15,000 people— around the size of Greenwood, MS— yet there are dozens of pancake houses.

There is the Colonial Pancake House, the Capital Pancake House, the National Pancake House, the Southern Pancake House, the Smokey Griddle Pancake House, Sandy’s Pancake House, the Old Chickahominy Pancake House, Mama Steve’s House of Pancakes, Five Brothers Pancake and Steak House, Old Mill House of Pancakes— I’m not making this up, Google it— Shorty’s Diner where they specialize in, you guessed it, pancakes, and my favorite name of all, The Astronomical Pancake House (someone dug deep into the thesaurus when naming that place, though they really didn’t have a choice because ALL of the other names for pancake houses were taken).

Author’s note—The aforementioned book, “Deep South Staples” is currently ranked an unimpressive number 1,483,175 in all books on Amazon.com. Though, coincidentally, it’s a number which directly correlates to the exact number of pancake houses in Williamsburg, VA.

We ate pancakes. We heard great music. Two brothers revisited a place that meant so much to our mother. Did I mention that we ate pancakes? We did. A lot of pancakes. We came, we saw, we tried on tri-cornered hats, and we ate pancakes. Now I need to go wash my hands.

Onward.