In 1982 I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my life. I had recently flunked out of college and had yet to fall in love with the restaurant business. I was living in a sketchy apartment complex behind a fraternity house at Millsaps College in Jackson. It was 12 years after Woodstock but the complex— a building that looked like an old motel full of colorful characters— felt like a leftover commune from the 1960s.

I was living on a very tight budget and found a boarding house several blocks away that served an inexpensive lunch and dinner. The old men who lived at the boarding house usually ate dinner before the general public was allowed to eat. I loved getting to the boarding house when the old men ate. It was a dual treat for me: The meal was less than $5.00 and the conversation was priceless.

There was usually meat, a few vegetables, some type of bread— a roll or cornbread— and iced tea. It was home-cooked food and it tasted pretty good. I would sit and listen to the old men as they solved the world’s problems. Several were World War II veterans and would occasionally tell stories of overseas battles.

I never engaged the men in conversation. I don’t know why. Maybe it was youth or intimidation, or maybe I was just clueless and only interested in getting a cheap meal and going about my business. I know that if I were given that same opportunity today I would be the most inquisitive person at the table.

Hitting up area boarding houses for cheap meals was a welcome change at that time. I had spent the previous semester at Mississippi State eating off of the $1.00 children’s menu at a Western Sizzlin’ restaurant for three months because I had traded my university meal ticket for a color television during registration. Boarding house cuisine was welcome fare.

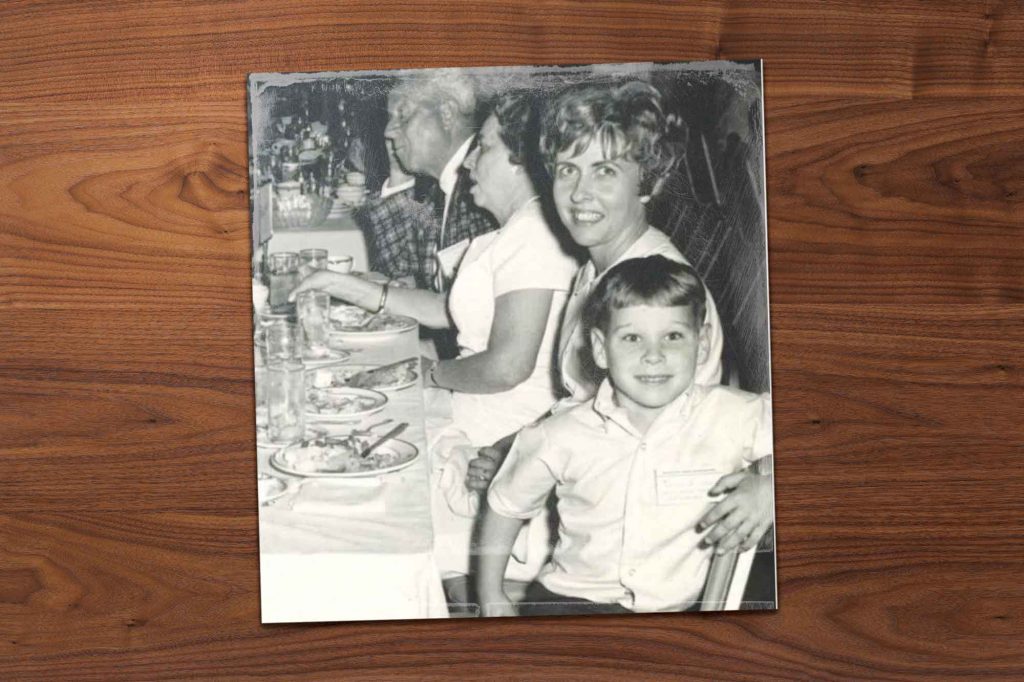

As a kid growing up in Hattiesburg I often ate lunch at a boarding house everyone called Ma Twilley’s. It was on Main Street a few blocks from the downtown businesses and courthouses. Customers walked along a tight ligustrum-lined sidewalk that ran the length of the boarding house and led to a back porch door where one entered through the kitchen.

Once inside customers paid for their lunch and helped themselves to vegetables, bread, and iced tea. The only people who handled the chicken were Ma Twilley, her daughter, or one of her kitchen helpers. Ma Twilley didn’t need a college textbook on the restaurant business to tell her that all of the money is in the protein.

Larry Foote grew up next door to Ma Twilley’s boarding house. “She was exactly like a Norman Rockwell painting of a grandmother,” Foote said. When I asked if he remembered the part about the staff serving the fried chicken, he remembered always getting his own, but added that he was to blame for the price of lunch increasing from 75 cents to $1 in the early 1950s because he ate so much chicken.

The food was good, it was real, and it was inexpensive. During lunch Ma Twilley’s seemed like a true slice of the community. There were lawyers and bankers from downtown, workmen on their lunch break, in from the hot sun and grateful for air conditioning, and students living on a budget. There were also boarders.

Boarding houses haven’t all gone away but have become a dying breed. Hattiesburg Mississippi had dozens during the 1940s when Camp Shelby housed over 100,000 soldiers. My grandmother once told me that during World War II anyone who had a spare bedroom rented it out to families of soldiers who were stationed at Camp Shelby.

I don’t know where all of the boarding houses have gone or why. Maybe they’ve all been converted to B&Bs. Maybe they’ve given way to extended stay hotels. All I know we are the lesser for it.

I don’t remember when Ma Twilley’s closed. I guess it was sometime in the mid 1980s. During those days I was back in school at Southern Miss studying the restaurant business and more interested in new dining trends as I was planning to open my first restaurant. Ma Twilley’s closed without much fanfare, just like Ma Redmond’s boarding house before it.

The problem with fading institutions and traditions is that they die a slow, almost unnoticeable, death. Shiny new things distract us and the old things get left behind. By the time we come back around— usually for nostalgia’s sake— the thing is gone. We tell ourselves, “I’ll get to that soon,” or “Someday we’ve got to get together and catch up,” or “We need to do that again.” Hopefully we do. We don’t dictate the calendar. We are at the mercy of time.

Sunday Dinner Biscuits

2 cups Flour, self-rising

1 /3 cup Shortening, butter or lard

2 /3 –3 /4 cup Milk or buttermilk

Preheat oven to 500 degrees.

Combine flour and shortening in mixing bowl. Work shortening pieces into flour with a pastry cutter until they are the size of small peas. Gradually stir in milk or buttermilk. Add only enough to moisten the flour and hold the dough together.

Transfer dough to a lightly floured surface. Knead gently two to three strokes. Using a light touch, pat or roll the dough to a 1 /4-inch thickness. Cut with a floured 2-inch biscuit cutter, leaving as little dough between cuts as possible. Gather remaining dough and re-roll one time. Discard scraps after second cutting.

Place biscuits on a baking sheet with sides touching for soft Southern-style biscuits. If you prefer biscuits with crisp sides, place biscuits close together but not touching.