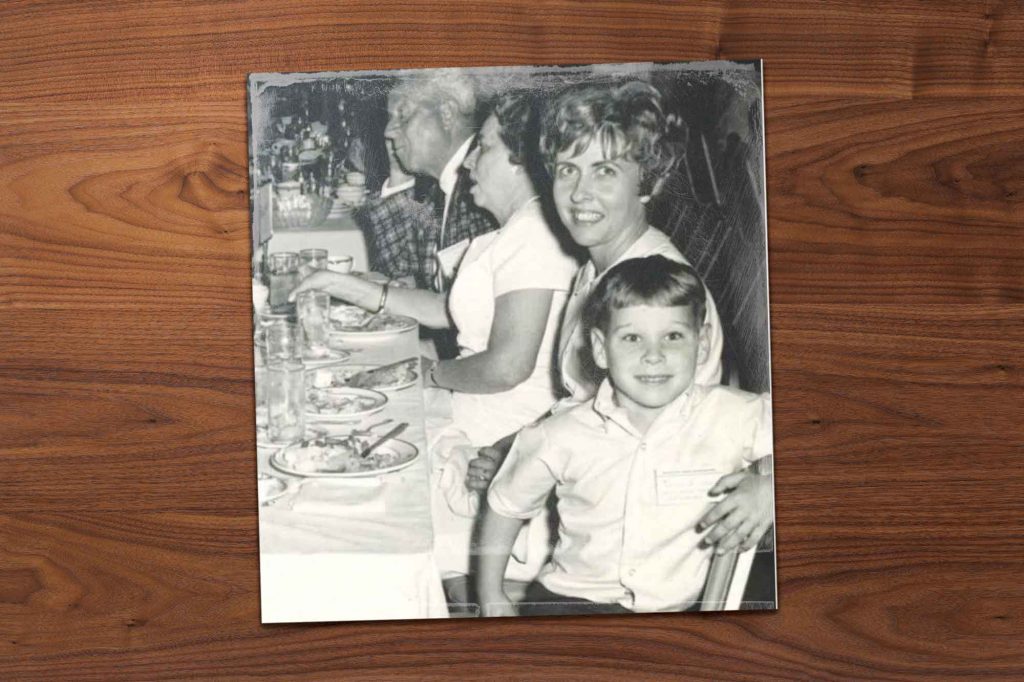

I grew up in a woman’s world.

Males tended to die young in my family. My father died when I was six-year’s old, my paternal grandfather, five years before that. For most of our childhood, my brother and I were the “men” of the family.

My mother was a fanatic about manners. She was a drill sergeant when it came to decorum, and Emily Post was her four-star general— when in doubt, consult the book. The book being “Emily Post’s Etiquette” (the second bible in our home), though I don’t ever remember her actually looking in the book. I just assumed that she had the entire thing memorized.

“Yes ma’am” and “No Ma’ams” were mandatory, and always required, no matter whom we were addressing. I was probably the only student at the First Presbyterian Kindergarten who was forced to put his napkin in his lap and knew the proper table placement of his plastic knife and fork.

Her strict adherence to the second bible in our home always became more rigid around mealtimes. The Victorian Age— the era that gave birth to Emily Post— was filled with rules and regulations about eating. Gilded Age diners had a utensil for everything: Asparagus forks, olive forks, sherbet spoons, and a partridge in a pear tree, blah, blah, blah.

Formal meals with my family were hard work. There was a mother, two grandmothers, a great-grandmother, a couple of aunts, and several female cousins. When it came time to finally sit down at the table, my brother and I would frantically rush around the table trying to help seat all of the ladies in the family. Two young boys pulling out a dozen chairs in a mad, pre-meal scramble that required a lot of precision and timing. “I’ll take the left side, you take the right. Go!” Once seated, we were sweaty, winded, and often too tired to eat.

That is, unless I pulled the hand-washing ploy. Out of all of the tricks in my brother-to-brother practical-joke cupboard (my mother would call it a chiffonier), the hand-washing ploy was one of my favorites.

The key to the successful execution of the hand-washing ploy was all in the timing. One had to excuse himself to wash his hands at just the precise moment.

That was the beauty of the hand-washing ploy. It was perfect in it’s structure . At its core it was all about manners. One should always ask to be excused, and one should always wash hands before a meal. Who could say no to that?

Again, timing was key. I would pick just the right amount of time before we sat down to lunch, and just enough time so that everyone would go ahead and sit down without waiting on me. This is when I would forego the bathroom, hide around the corner, and watch my brother try to seat all of the ladies in our family by himself. He worked overtime, sweating, stumbling, constantly looking out of the corner of his eye waiting for me to return, but knowing down deep that I wouldn’t, and finally realizing that he had been zinged again.

Ultimately, the reason St. John men died young is because the women in the family had us working overtime on table manners.

My high school graduation gift from my mother was— you guessed it— a copy of, “Emily Post’s Etiquette,” because every incoming college freshman who attends a frat party with a punk band and a trash can full of grain-alcohol whoop juice needs to be able to say, “I want to make you acquainted with Miss Smith.” And, “Pardon me. Pleased to meet you. Will you permit me to recall myself to you?”

The World’s Last Deviled Egg

1 dozen Eggs, hard boiled, peeled and cut in half, lengthwise

2 tsp. White balsamic vinegar

1 /3 cup Mayonnaise

1 /4 cup Sour cream

1 TBL pickle relish

1 1 /2 tsp Salt

1 Tbl Creole Mustard

2 tsp yellow mustard

1 /8 tsp white pepper

1 /8 tsp Garlic, granulated

Paprika and fresh parsley to garnish (optional)

Remove the yolks from the hard cooked eggs and place in a mixing bowl. Add all ingredients and beat with an electric mixer until smooth. Use a pastry bag to fill the egg whites. Sprinkle with paprika fresh parsley.

Yield: 24